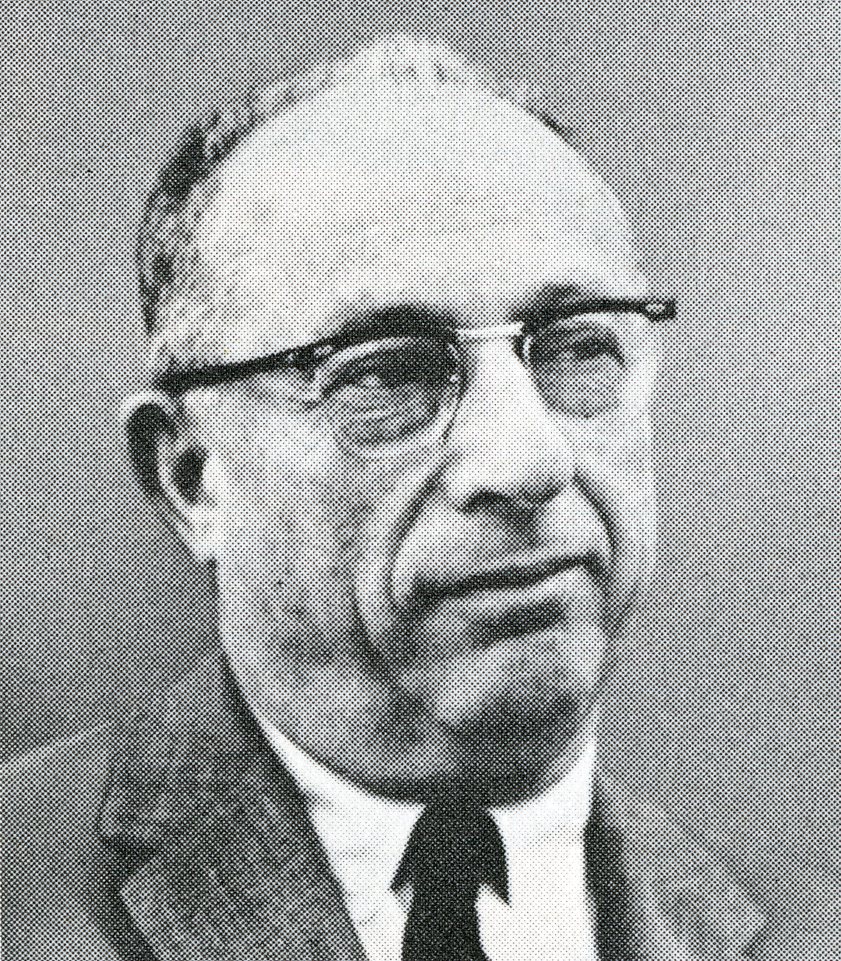

I am one of four people who addressed Rabbi Olan as Papa – because he was my grandfather. When I was growing up in Dallas during the 1960s and 1970s – going to religious school once a week at Temple Emanuel, attending High Holy Day services, attending family brunches with deli from Ernie’s, and becoming a bar mitzvah – Papa was a larger-than-life presence in my life.

I vaguely recall his sermons in the Temple’s grand main synagogue as being endless affairs (to my young person’s attention span) – erudite, sprinkled with humor, delivered in a voice that was slow, sonorous, and cultured, which sometimes trailed off into long s’s and sometimes rose to majestic heights. These heights were generally associated with what I would later come to recognize as his prophetic voice, his insistence that the generally well-off congregants to whom he was speaking had a duty – an urgent moral duty – to reject selfish materialism and devote themselves to the welfare of the poor and oppressed. I may have found Papa’s sermons to be boring and overlong, but somehow at the same time I absorbed that message so deeply that it became one of the immutable building blocks of my consciousness, a building block that, half a century later, continues to structure how I think about the world and my place in it.

I don’t think the nature of that building block has been altered in my consciousness one iota by the fifty years of living I have experienced since. It’s why I find myself either unable or unwilling to work a job in the for-profit sector. It’s why I’ve spent a good deal of my life as a social justice activist and been arrested three times for civil disobedience. Sometimes it creates discomfort, when, in my personal or professional life, I insist on some action I believe is necessitated by Papa’s prophetic message but that will inconvenience those around me.

But as I’ve listened to, read, and written about his radio sermons these past few years – not surprisingly – my relationship with them hasn’t been that simple. Some of the sermons have conformed to my memory of him declaiming his prophetic message from the pulpit. Others have not. I found some to be not as well written or as compelling as others. Some contained opinions with which I do not agree.

My most common disagreement has been with his frequently articulated argument for the existence of God and against atheism. Not the fact that he made that argument – that shouldn’t be surprising for a rabbi – but how he argued it. He argued that atheism renders human existence meaningless and amoral. I’m no expert on atheism, but I suspect it’s not that simple. I wish he had trained that big brain of his on a deeper analysis of the question, because I would like to know what he would have said. (I haven’t read all his writing, so maybe he did elsewhere.)

In addition, God never seemed to me to play a role in that limited part of his personal life to which I was a witness. I don’t know what conclusion to draw from that; unfortunately, I can’t ask him.

I debated whether to bring up some of these latter points here, for fear of knocking the saint off his pedestal. But I came to the conclusion that it makes for a more interesting story if, despite learning some things I don’t like, I can still honor the part of my Papa that became ingrained in me. Part of that is a belief in truth, and I think he would have wanted me to be truthful.

*Written by Joshua F. Hirsch*